Story by Angelo Misthos

Note: “Optimism does not a success make”–June quote

Created by June Morrall

Story by Angelo Misthos

Note: “Optimism does not a success make”–June quote

|

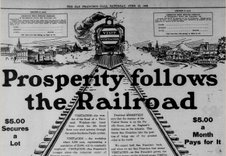

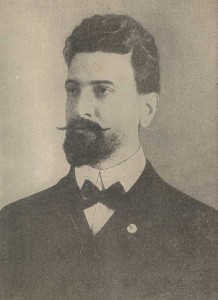

Downey Harvey was president of the Ocean Shore Railway

By June Morrall

In 1906, the rolling hills of San Mateo seemed an unlikely site for an English fox hunt, replete with traditional riding regalia, fine horses and a full complement of hounds. All that was missing was the fox. This did not deter the resourceful Peninsula aristocrats. If local foxes were scarce, coyotes weren’t.

From a distance, the men and women astride galloping horses looked like specks of red and black, impressionistic figures on the San Mateo landscape. Attired in red hunting jackets, white breeches and black caps, they were members of the San Mateo County Hunt Club.

As “master of the San Mateo Hounds,” John Downey Harvey, the 46-year-old president of the Ocean Shore Railway, gathered around him the “regulars.” Thesemembers included Harvey’s daughters, Anita and Genevive, his friend, attorney Francis Carolan, banker Richard Tobin and polo players Captain Seymour and Walter Hobart. The Burlingame Country Club was the meeting place for the “drag hunt,” which resembled a fox hunt, except the hounds were trained to follow an artificial scent.

As the riders and their hounds nervously awaited the start of the meet covering 15 miles, none of them dreamed that a month later, the San Francisco earthquake and fire would change many of their lives. The Peninsula’s great water mains would collapse as San Mateo County sustained wide quake damage.

On the Coastside, boulders would tumble over Devil’s Slide into the foaming surf, followed by the twisted remains of the Ocean Shore Railroad’s freshly laid track and expensive rolling stock.

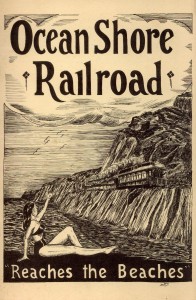

As owner of 13,000 shares of the railway, Downey Harvey was the driving force behind the first railroad to promote a 5 ½ – hour trip as a moving picture ride down the San Mateo County Coastside, featuring views of cliffs, bluffs, beaches, rocks, redwoods and marine scenery.

While the San Mateo County Hunt Club met, Downey Harvey didn’t have earthquakes or any dark thoughts on his mind as his horse “Fawn” jumped the five-foot fences. On the contrary, the railway president felt a burst of energy as the small pack of hounds led the hunters at a galloping speed across familiar terrain: fields bordering banker W.H. Crocker’s home called “New Place;” millionaire executive and future Hillsborough mayor Robert Hooker’s estate; the gate of Francis and Harriet Carolan’s Crossways Farm; the back of the Tevis place, later Jennie Crocker’s home; the golf links of the Burlingame Country Club and the shade trees of “Howard’s Woods.”

Born in Los Angeles on April 17, 1860, J. Downey Harvey was the son of Colonel Walter and Eleanor Harvey. His uncle, John G. Downey, was the seventh governor of California, later a business partner of Alvinza Hayward, whose mansion once stood near Ninth Avenue in San Mateo.

When Downey was 10-years-old, his father, Harvey, died. With his mother, Eleanor, who had married banker Edward Martin, Downey moved to San Francisco. Dubbed “Queen” Eleanor, Downey’s mom became the undisputed leader of San Francisco society for decades, and her home was known as a “fortress of respectability.”

As a youngster, Downey Harvey displayed a “genius” for acquiring friends. In school, he befriended the son of Pio Pico, the last governor of Alta California, who, with his family chose to reside in Los Angeles. Harvey also knew John C. Fremont, a popular, nationally known figure, and a promoter of railroad projects in the West.

In 1883, 23-year-old Downey Harvey married Sophie Cutter; the couple raised two daughters, Anita and Genevive. Sophie Harvey loved music and a full social calendar, yet she managed to run her large household with efficiency.

Along the way, Downey collected all types of friends. from artists and entertainers to business and military men. His aspiration was to become a “clubman.”

By 1895, Downey, an avid sportsman, reportedly laid out Northern California’s first golf course for the San Francisco Golf and Country Club. When he learned that San Mateo County, because of its “undulating pasture without pebbles,” was the best terrain for the hunt, he focused his efforts on helping develop the San Mateo County Hunt Club.

Polo player Walter Hobart had a place in the hunt club’s lore. In 1897, he purchased 38 foxhounds, shipping them from New York to San Mateo for the first “authentic” chase. The San Mateo County Hunt Club members pursued Hobart’s hounds across the fields in a “drag hunt,” the animals chasing a sack of anise seed, a flavoring used in alcoholic drinks called “cordials.” The hunt ended when the hounds surrounded the aromatic sack. Disappointed that their quarry was not alive, the hounds had to be rewarded with stewed beef. As for the hunt club members, they rode back to the Burlingame Country Club for cocktails and dinner, followed by a big party.

Their aristocratic English fox-hunting cousins would have found many deficiencies in the San Mateo club’s version of the hunt. One one occasion the “clever huntsman” Jerry Keating unleashed a large pack of hounds, so many that they were in every field, in every direction.

Making matters worse (or perhaps more exciting), so-called “unauthorized horsemen” (folks who “just” enjoyed riding) put themselves between the hunters and the dogs. Foiling the scent with their steaming horses, they tested the patience of the master of the hunt, ruining the chase.

Ocean Shore Railway President J. Downey Harvey learned from Jerry Keating’s mistakes, and he never brought along too many hounds.

Harvey also did not like to be called by his official title, “master of the San Mateo Hounds.”

“His democratic ideas,” explained a friend, “coupled with his modesty and his kindliness will not allow him to bear the honorable title which means so much to European sportsmen.”

Harvey had always displayed an interest in horses, as did his close friend San Francisco attorney Francis Carolan. Married to Harriet Pullman, heiress to the railroad car fortune, Carolan loved his equine friends, but it was more than just a hobby. Offered top dollar for Vidette, one of the best jumpers in the country, the attorney repeatedly refused to sell his favorite hunting horse at any price.

Upon completion of the Carolan’s Crossways Farm, a Burlingame residence with stables and a private polo field, the couple celebrated with a spectacular party held inside the stables. Flower-draped chartered Pullman cars carried guests–the men attired in red hunting jackets–from San Francisco to the Burlingame farm. Thousands of Japanese lanterns (perhaps to show support for Japan, then at war with Russia) and electric lights lit up the grounds, and a multi-colored chandelier had been installed in the stables, according to the archives of the San Mateo County History Museum. To get a powerful boost of illumination, including a string of lights outlining the house, wires were strung all the way from Burlingame to Redwood City.

Cocktails and supper were served at tables placed near the brightly lit stables; entertainment included a Japanese ballet and Spanish dancers.

The Carolans became famous for the renowned French chateau they built in Hillsborough in 1915 — abandoned by them seven seven months later — when the rattling windows and other annoyances undermined their shaky marriage, causing them to abruptly leave the Carolans and each other.

As a major shareholder of Ocean Shore Railroad stock, it was natural that Downey Harvey would think about the railroad’s difficult construction near Devil’s Slide, north of Montara on the Coastside. Building a railroad along the coast route from San Francisco to Santa Cruz had been strewn with obstacles.

Forty years earlier in 1865, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company surveyed the possibility of a Coastside railroad, creating an air of excitement in Pescadero and Half Moon Bay. Thousands of workers were slated to fell trees, excavate cuts, string bridges and bore tunnels. Suddenly land prices doubled….but the bubble burst, and the railroad was not built.

Millionaire miner Alvinza Hayward, who built a mansion [later turned into a hotel] in San Mateo, spent $17,000 surveying a railroad, doing some grading and securing rights-of-way. His plans suddenly were dropped because of bad investments.

Other planned railroads failed as well. In 1905 the San Mateo Times, fearing interference from the Western Pacific Railroad, called for their choice, the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) to take action.

The San Mateo Times implored the SP to spend money encouraging a Coastside railroad from Santa Cruz to San Francisco. If they did this, the San Mateo Times held, the SP would shut out “dangerous competition and forever make the counties of Santa Cruz, San Mateo and San Francisco the exclusive territory for the construction of the Southern Pacific railroads.”

The SP'[s engineering department responded that a surveying party had begun, and the company was acquiring the rights-of-way. The SP’s efforts came too late, for Downey Harvey and his independent group of Ocean Shore Railway investors had outmaneuvered the competition.

Inviting guests to his new home, San Francisco Mayor Eugene Schmitz [Image: San Francisco Mayor Eugene Schmitz]

proudly showed visitors a $1,250 Persian rug–a lavish gift reportedly from Downey Harvey, thus greasing the skids for the Ocean Shore Railway being awarded the coveted San Francisco franchise.

In 1906, a month before the earthquake struck, the San Mateo Hunt Club members, hot on the trail of the hounds disappeared into the tree-lined Howard Woods where a “coyote was liberated and killed by the pack.” The hounds backtracked over the same course while Downey Harvey and the other hunters rode to the Burlingame clubhouse where they enjoyed luncheon on the verandah. The day of sport had not ended for polo players Captain Seymour and Walter Hobart; these men galloped off for a polo match at Francis Carolan’s nearby private polo field.

A month later, on April 18, the San Francisco earthquake struck.

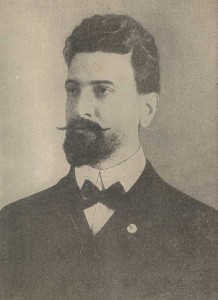

(Image from a book called: “Complete Story of the San Francisco Horror,” Memorial Edition. 1906)

As president of the Ocean Shore Railway, Downey Harvey convinced San Francisco’s mayor to form a Committee of Fifty to provide relief for the homeless, but his own losses were beyond calculation.

Author Gertrude Atherton wrote that her friend Downey Harvey had invested the greater part of his fortune in the Coastside’s scenic railway–but after the earthquake there was little interest in scenic railroads and new resorts.

The Ocean Shore limped for4ward but the Harveys had lost so much money in the railroad they were forced to live in a sort of retirement for awhile. For the Downey Harveys, such a retirement meant living at Del Monte, the exclusive resort built by the Southern Pacific Railroad at Monterey.

Upon his return to San Francisco, Downey Harvey faced lawsuits resulting from the tragic death of an Ocean Shore train conductor. The OSRR finally closed down about 1922.

J. Downey Harvey, whose affiliations included the Bohemian, Pacific Union, Olympic and San Francisco Golf Clubs, was “the most human of human beings,” said a friend after his death in 1947. “He had the wisdom of a fox and honesty of a sunrise.

———

I wrote this story some years ago.

—–

Hi June,

In 1906, the rolling hills of San Mateo seemed an unlikely site for an English fox hunt, replete with traditional riding regalia, fine horses and a full complement of hounds. All that was missing was the fox. This did not deter the resourceful Peninsula aristocrats. If local foxes were scarce, coyotes weren’t.

From a distance, the men and women astride galloping horses looked like specks of red and black, impressionistic figures on the San Mateo landscape. Attired in red hunting jackets, white breeches and black caps, they were members of the San Mateo County Hunt Club.

As “master of the San Mateo Hounds,” John Downey Harvey, the 46-year-old president of the Ocean Shore Railway, gathered around him the “regulars.” These members included Harvey’s daughters, Anita and Genevive, his friend, attorney Francis Carolan, banker Richard Tobin and polo players Captain Seymour and Walter Hobart. The Burlingame Country Club was the meeting place for the “drag hunt,” which resembled a fox hunt, except the hounds were trained to follow an artificial scent.

As the riders and their hounds nervously awaited the start of the meet covering 15 miles, none of them dreamed that a month later, the San Francisco earthquake and fire would change many of their lives. The Peninsula’s great water mains would collapse as San Mateo County sustained wide quake damage.

On the Coastside, boulders would tumble over Devil’s Slide into the foaming surf, followed by the twisted remains of the Ocean Shore Railroad’s freshly laid track and expensive rolling stock.

As owner of 13,000 shares of the railway, Downey Harvey was the driving force behind the first railroad to promote a 5 ½ – hour trip as a moving picture ride down the San Mateo County Coastside, featuring views of cliffs, bluffs, beaches, rocks, redwoods and marine scenery.

While the San Mateo County Hunt Club met, Downey Harvey didn’t have earthquakes or any dark thoughts on his mind as his horse “Fawn” jumped the five-foot fences. On the contrary, the railway president felt a burst of energy as the small pack of hounds led the hunters at a galloping speed across familiar terrain: fields bordering banker W.H. Crocker’s home called “New Place;” millionaire executive and future Hillsborough mayor Robert Hooker’s estate; the gate of Francis and Harriet Carolan’s Crossways Farm; the back of the Tevis place, later Jennie Crocker’s home; the golf links of the Burlingame Country Club and the shade trees of “Howard’s Woods.”

Born in Los Angeles on April 17, 1860, J. Downey Harvey was the son of Colonel Walter and Eleanor Harvey. His uncle, John G. Downey, was the seventh governor of California, later a business partner of Alvinza Hayward, whose mansion once stood near Ninth Avenue in San Mateo.

When Downey was 10-years-old, his father, Harvey, died. With his mother, Eleanor, who had married banker Edward Martin, Downey moved to San Francisco. Dubbed “Queen” Eleanor, Downey’s mom became the undisputed leader of San Francisco society for decades, and her home was known as a “fortress of respectability.”

As a youngster, Downey Harvey displayed a “genius” for acquiring friends. In school, he befriended the son of Pio Pico, the last governor of Alta California, who, with his family chose to reside in Los Angeles. Harvey also knew John C. Fremont, a popular, nationally known figure, and a promoter of railroad projects in the West.

In 1883, 23-year-old Downey Harvey married Sophie Cutter; the couple raised two daughters, Anita and Genevive. Sophie Harvey loved music and a full social calendar, yet she managed to run her large household with efficiency.

Along the way, Downey collected all types of friends. from artists and entertainers to business and military men. His aspiration was to become a “clubman.”

By 1895, Downey, an avid sportsman, reportedly laid out Northern California’s first golf course for the San Francisco Golf and Country Club. When he learned that San Mateo County, because of its “undulating pasture without pebbles,” was the best terrain for the hunt, he focused his efforts on helping develop the San Mateo County Hunt Club.

Polo player Walter Hobart had a place in the hunt club’s lore. In 1897, he purchased 38 foxhounds, shipping them from New York to San Mateo for the first “authentic” chase. The San Mateo County Hunt Club members pursued Hobart’s hounds across the fields in a “drag hunt,” the animals chasing a sack of anise seed, a flavoring used in alcoholic drinks called “cordials.” The hunt ended when the hounds surrounded the aromatic sack. Disappointed that their quarry was not alive, the hounds had to be rewarded with stewed beef. As for the hunt club members, they rode back to the Burlingame Country Club for cocktails and dinner, followed by a big party.

Their aristocratic English fox-hunting cousins would have found many deficiencies in the San Mateo club’s version of the hunt. One one occasion the “clever huntsman” Jerry Keating unleashed a large pack of hounds, so many that they were in every field, in every direction.

Making matters worse (or perhaps more exciting), so-called “unauthorized horsemen” (folks who “just” enjoyed riding) put themselves between the hunters and the dogs. Foiling the scent with their steaming horses, they tested the patience of the master of the hunt, ruining the chase.

Ocean Shore Railway President J. Downey Harvey learned from Jerry Keating’s mistakes, and he never brought along too many hounds.

Harvey also did not like to be called by his official title, “master of the San Mateo Hounds.”

“His democratic ideas,” explained a friend, “coupled with his modesty and his kindliness will not allow him to bear the honorable title which means so much to European sportsmen.”

Harvey had always displayed an interest in horses, as did his close friend San Francisco attorney Francis Carolan. Married to Harriet Pullman, heiress to the railroad car fortune, Carolan loved his equine friends, but it was more than just a hobby. Offered top dollar for Vidette, one of the best jumpers in the country, the attorney repeatedly refused to sell his favorite hunting horse at any price.

Upon completion of the Carolan’s Crossways Farm, a Burlingame residence with stables and a private polo field, the couple celebrated with a spectacular party held inside the stables. Flower-draped chartered Pullman cars carried guests–the men attired in red hunting jackets–from San Francisco to the Burlingame farm. Thousands of Japanese lanterns (perhaps to show support for Japan, then at war with Russia) and electric lights lit up the grounds, and a multi-colored chandelier had been installed in the stables, according to the archives of the San Mateo County History Museum. To get a powerful boost of illumination, including a string of lights outlining the house, wires were strung all the way from Burlingame to Redwood City.

Cocktails and supper were served at tables placed near the brightly lit stables; entertainment included a Japanese ballet and Spanish dancers.

The Carolans became famous for the renowned French chateau they built in Hillsborough in 1915 — abandoned by them seven seven months later — when the rattling windows and other annoyances undermined their shaky marriage, causing them to abruptly leave the Carolans and each other.

As a major shareholder of Ocean Shore Railroad stock, it was natural that Downey Harvey would think about the railroad’s difficult construction near Devil’s Slide, north of Montara on the Coastside. Building a railroad along the coast route from San Francisco to Santa Cruz had been strewn with obstacles.

Forty years earlier in 1865, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company surveyed the possibility of a Coastside railroad, creating an air of excitement in Pescadero and Half Moon Bay. Thousands of workers were slated to fell trees, excavate cuts, string bridges and bore tunnels. Suddenly land prices doubled….but the bubble burst, and the railroad was not built.

Millionaire miner Alvinza Hayward, who built a mansion [later turned into a hotel] in San Mateo, spent $17,000 surveying a railroad, doing some grading and securing rights-of-way. His plans suddenly were dropped because of bad investments.

Other planned railroads failed as well. In 1905 the San Mateo Times, fearing interference from the Western Pacific Railroad, called for their choice, the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) to take action.

The San Mateo Times implored the SP to spend money encouraging a Coastside railroad from Santa Cruz to San Francisco. If they did this, the San Mateo Times held, the SP would shut out “dangerous competition and forever make the counties of Santa Cruz, San Mateo and San Francisco the exclusive territory for the construction of the Southern Pacific railroads.”

The SP'[s engineering department responded that a surveying party had begun, and the company was acquiring the rights-of-way. The SP’s efforts came too late, for Downey Harvey and his independent group of Ocean Shore Railway investors had outmaneuvered the competition.

Inviting guests to his new home, San Francisco Mayor Eugene Schmitz [Image: San Francisco Mayor Eugene Schmitz]

proudly showed visitors a $1,250 Persian rug–a lavish gift reportedly from Downey Harvey, thus greasing the skids for the Ocean Shore Railway being awarded the coveted San Francisco franchise.

In 1906, a month before the earthquake struck, the San Mateo Hunt Club members, hot on the trail of the hounds disappeared into the tree-lined Howard Woods where a “coyote was liberated and killed by the pack.” The hounds backtracked over the same course while Downey Harvey and the other hunters rode to the Burlingame clubhouse where they enjoyed luncheon on the verandah. The day of sport had not ended for polo players Captain Seymour and Walter Hobart; these men galloped off for a polo match at Francis Carolan’s nearby private polo field.

A month later, on April 18, the San Francisco earthquake struck.

(Image from a book called: “Complete Story of the San Francisco Horror,” Memorial Edition. 1906)

More coming

As president of the Ocean Shore Railway, Downey Harvey convinced San Francisco’s mayor to form a Committee of Fifty to provide relief for the homeless, but his own losses were beyond calculation.

Author Gertrude Atherton wrote that her friend Downey Harvey had invested the greater part of his fortune in the Coastside’s scenic railway–but after the earthquake there was little interest in scenic railroads and new resorts.

The Ocean Shore limped for4ward but the Harveys had lost so much money in the railroad they were forced to live in a sort of retirement for awhile. For the Downey Harveys, such a retirement meant living at Del Monte, the exclusive resort built by the Southern Pacific Railroad at Monterey.

Upon his return to San Francisco, Downey Harvey faced lawsuits resulting from the tragic death of an Ocean Shore train conductor. The OSRR finally closed down about 1922.

J. Downey Harvey, whose affiliations included the Bohemian, Pacific Union, Olympic and San Francisco Golf Clubs, was “the most human of human beings,” said a friend after his death in 1947. “He had the wisdom of a fox and honesty of a sunrise.”

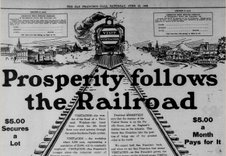

From the San Mateo County History Museum

Wave Crest, December 18, 1905

Arleta Park, January 15, 1906

Miramar, February 19, 1906

Grandview Terrace, April 9, 1906

Farallone City, June 2, 1906

Lipton-by-the-Sea, September 27, 1906

Manhattan Beach, March 18, 1907

Venice Beach, May 6, 1907

Montara, June 3, 1907

City of Naples, September 10, 1907

El Granada, November 18, 1907

Redondo Beach, December 2, 1907

Moss Beach, May 4, 1908

Princeton-by-the-Sea, September 8, 1908

Marine View, July 6, 1909

Hello June.

Some of your readers interested in the Ocean Shore R.R. may not know that efforts to resurrect it began almost as soon as it was abandoned. Jack Wagner’s THE LAST WHISTLE is the best reference.

I recall several San Francisco newspaper articles during the 1930s; and as a teenager I got up the nerve to go to the company’s office in downtown S.F. to inquire of its progress, and met the President, George Middleton. The office was shared with a mining company–either Alaska-Juneau Gold Mining or Bunker Hill. I can’t remember and don’t know of any relationship with the new OSRR.

Mr. Middleton said the line would re-enter San Francisco by the old, seldom-used Southern Pacific’s Ocean View line. That track was now in the heavily built-up Mission District where people in homes could practically shake hands with the engine crew if a train ever went by. I remember being skeptical that the City would permit it.

Apropos of that time, I have a copy of the December, 1935, issue of “Railroad Stories” magazine and the article “The Ocean Shore Comes Back” by G. H. Kneiss, which told of the expected rebuilding, mainly to exploit the timber resources of the Butano Forest, close to the original route, but never reached.

There are a number of court cases involving the OSRR from that time on the Internet, mainly dealing with the railroad’s suits for incursions on its former right-of-way, some becoming precedents for other cases.

One of the more interesting is a 1941 appeal re an earlier decision about the injury from falling rocks in June, 1936, to a power shovel operator engaged by the railroad to clear the blocked north portal of the Pedro Point tunnel. A few months earlier the shovel had been “almost completely buried” by a slide at the south portal. I find it almost incredible how the shovel made it to the south portal.

This was before Hwy. 1 had been re-routed closer to the coast, and so the shovel had to have taken the long route past Green Canyon and over Devil’s Slide on a roadbed neglected for over fifteen years. What problems the operator encountered can only be imagined. Mr. Wagner’s book chronicled how all these efforts came to naught.

Angelo

These were published long after the Ocean Shore Railroad expired by the Western Railroaders.

Here’s Barbara Vanderwerf’s acclaimed book (and the only one that focuses on “Granada“.)

More recently, former Pacifica Tribune editor, Chris Hunter, wrote a well-received book about the Ocean Shore for Arcadia, for more info, click here

Here’s the granddaddy of all the Ocean Shore Railroad Books, and I think the best one: The Last Whistle by Jack Wagner

(Photo: Is this the Ocean Shore Railroad smokin’ through Pacifica?)

(Photo: Is this the Ocean Shore Railroad smokin’ through Pacifica?)

Mr. Vonderlin, I’ve enjoyed reading Half Moon Bay Memories and El Granada Observer as well as your Pescadero Memories, particularly references to the OSRR, which I became acquainted with in the late 1920s.

My uncle took my brother and me on a hike along the right-of-way from Thornton to Mussel Rock. Though the rails had been torn up, still it was obvious a railroad had been there.

In 1939 I made several bike trips down the coast from San Francisco, once climbing to the top of the collapsed tunnel at Pedro Point to view the grade south to Devil’s Slide. And I also drove to Santa Cruz in a friend’s Model A Ford, borrowed from his brother, always looking for OSRR remnants.

At Pescadero beach it looked like grading of the dunes had been done south of the “mysterious tunnel” bluff you described. On a much later visit I found the tunnel portal, and since the grading I’d seen earlier would have led to the tunnel site, I surmised that the OSRR had built the tunnel either as a pilot bore, or to use it to blow down the hillside for easier grading.

Your north portal pictures puzzle me as they don’t appear to coincide with this surmise. I’ve never seen anything about this in the OSRR literature.

Re the Palmer Gulch Trestle: I have a photo of it given to me in 1939 that shows the trestle had already started to sag in the middle. About 1960 a friend and I hiked down to it; by then it was sagging noticeably. On the north side was a large, weathered (tool?) box, about 12’x4’x4′ roughly. It had an old padlock on it which we left as is.

We walked across the trestle, and my friend took pictures, of which I have a couple. Unfortunately, they are now badly faded (Polaroid camera?). but the rotted ties are still evident. I don’t believe it burned down because I saw an internet picture of it taken a few years after our crossing, and it was in nearly collapsed condition, and the text said it totally collapsed shortly after. Regrettably I didn’t add it to my OSRR “favorites,” and have never found it on the Web again.

Thanks again for your interesting memories of the San Mateo coastside.

Angelo Misthos, Sebastopol CA.

————————————–

John Vonderlin replies

(email John: [email protected])

Hi June,

I received this interesting email today. It reminded me the tunnel (s) story is not a mystery solved. I’ll get back to it. The gentleman from the cemetery has said he’ll show us it, so maybe it exists. I sent Angelo a picture of a burnt timber, though that might have happened after collapse. I loved that he lives in Sebastopol. I used to have a wonderful ranch/family orchard in the hills west of town during the Seventies. George Lichty, the cartoonist of “Grin and Bear It,” fame lived across the street. The Thomases who owned the American Opinion Bookstore (John Birch Society–remember them?) were at one corner, two gay interior designers from S.F. on another and a schoolteacher couple who were Sufis on another. A great time in my life to recall. Where has my youth gone?

Larry Fitterer and I are going to be lowering ourselves down the cliffs into “The Notch” and Acid Beach on April 9th or 10th. Yee-Haw. Hopefully, I won’t break my typing fingers or anything else. Enjoy. John