I wrote this in 1977. The story was researched at the San Mateo County History Museum.

While Jurgen F. Wienke lay awake, staring at the ceiling, wife Meta dozed peacefully beside him. Instead of sleeping, Wienke, who built the fashionable Moss Beach Hotel overlooking the gray-blue Pacific, reflected on recent happenings at his resort.

It was the 1890s, and famous scientists often arrived to study the remarkable marine plant life there.

Why only last weekend, Jurgen was thinking, David Starr Jordan, the first president of Senator Leland Stanford’s university in Palo Alto, signed the hotel register.

Jurgen, who enjoyed the title of “Mayor of Moss Beach,” glowed with pride. He knew he had reached the pinnacle of local success when his most prominent guests braved a twisting mountain road to reach his resort near the cliffs of beautiful Moss Beach.

As the Mayor contemplated the long hours of dedicated work, he thought he heard gunfire above the sound of the crashing waves. In a split second his mind returned from reverie to the present. What was that?

A ship’s horn blared in the distance. Curiosity fully aroused, Wienke bounced out of bed, and without disturbing his still-sleeping wife, changed into outdoor apparel. He tip-toed past daughter Lizzie’s bedroom and slipped out the front door.

It was dawn.

Once outside, Mayor Wienke listened for more clues. As he walked briskly among the rows of cypress trees he had planted, he remembered nourishing them through several periods of drought. Again, the sound of a ship’s horn jarred Wienke’s thoughts back into the present.

He glanced out to sea but the fog concealed anything that might have been there. Then, that sound again, the sound of a ship’s horn. This time he went back to the hotel, mounted his horse, and rode right toward the sound.

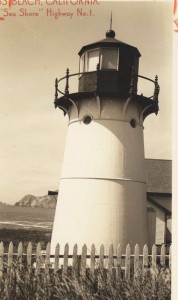

He rode as far north as the Point Montara Fog Station where several people were running toward the sandy beach. The mayor recognized David Splain and his daughter among them. He called out to David, the fog station’s caretaker, and rode fast to catch up with them.

David Splain told Mayor Wienke that a ship struck the jagged reefs (it was the third to do so at the same place.) Wienke wasn’t surprised. He said that most sailors called Point Montara a dangerous part of this stretch of coast.

And then the thick fog lifted, like a stage curtain, revealing the hazy outline of a schooner stranded on the rocks.

Splain and Wienke launched a small boat through the breakers, and as they rowed against the heavy surf, the outline of the ship’s captain appeared on the deck. He was Captain George C. Lovdal, he said. What’s my location? Where am I?

“Point Montara,” Mayor Wienke shouted but he was closed enough to see that Captain Lovdal was astonished.

As the fog kept burning off, Capt. Lovdal and his men prepared to leave the schooner. Some of them returned in Wienke’s little boat. By noon the shipwrecked crew stood on the cliffs above the sea wringing out their drenched clothing. Scores of spectators stood in clusters on the beach watching the waves crash over the ship’s bow. At low tide, in the afternoon, some of them waded through the surf to the vessel, hoping to collect a souvenir.

From the safety of shore, Capt. Lovdal surveyed the scene. He inspected the splintered boards and timbers, freshly tossed from the sea, now littering the sandy beach. He voiced little hope for his valuable cargo of lumber. This was a big loss and the captain strolled back and forth, with head lowered.

A reporter approached and him, wanting details of the wreck. Capt. Lovdal identified his vessel as the “Argonaut,” adding that he left Coos Bay, Oregon a week earlier, bound for San Francisco with 300,000 feet of lumber and five ship’s spars.

But, Capt. Lovdal added ominously, a heavy blanket of fog accompanied them the entire voyage, a sign of bad luck. They reached Point Reyes on schedule. From there, as the captain steered for San Francisco, a strong southerly current swept the “Argonaut” way off course, 18 miles off course.

When he heard the fog signal, Lovdal still thought he was near Point Bonita [which explains why he was surprised to learn from Wienke that he struck the reef at Point Montara.] The “Argonaut’s” crew rushed to the bow where they discovered the huge breakers, then watched helplessly as their ship smashed onto the reefs where she remained stranded with a disabled rudder.

As Captain Lovdal’s crew went back to Wienke’s hotel, the captain rode with the reporter to Half Moon Bay where he telegraphed the “Argonaut’s” owners. In town, the conversation focussed on the local election held that day–but soon, details of the shipwreck overshadowed the number of votes cast for this one or that one.

With Captain Lovdal as the town’s unexpected guest, the organizers of the Methodist Ladies’ Election Supper committee invited him to join their celebration later that evening. At dinner, Captain Lovdal charmed everyone, joking that while he had been shipwrecked six times, never before had he been cast among so many good people, such beautiful women and delicious food.

Captain Lovdal was quite the smoothie.

The crew slept at the Mayor’s hotel and the next day a tug from San Francisco failed to free the “Argonaut” from claws of the rocky reef. Left with no other alternatives, the “Argonaut’s” owners auctioned the ship to the highest bidder. Wreckers arrived to salvage the cargo, sails and rigging. But few locals believed the wreckers would turn a tidy profit because they employed a lot of men at high wages, and the heavy seas impaired their work.

Mayor Wienke and Captain Lovdal stood on the windy bluffs and commiserated. They talked about the short distance between the fog whistle at Point Montara and Point Bonita in San Francisco. Anyone could easily mistake one for the other, Wienke said.

Later, the men relaxed at the Moss Beach hotel.

In the pleasant surroundings, Lovdal learned that the enterprising proprietor had been adding on room after room to accommodate the increasing flow of guests. Wienke and his wife even turned away visitors for lack of space.

During the course of the conversation, Wienke recounted his personal history. He told Lovdal that he left Germany at age 25, sailing for California where he mined and farmed. Fate stepped in to change all that one day in 1881.

As a younger Jurgen Wienke stood on Kearney Street in San Francisco, he noticed the sign which read: “Quinn & Muller: Halfmoon Bay Colony.”

Intrigued, he knocked on the door. The real estate agents told him that 3,000-acres, bounded by mountains and sea, were for sale. The land had belonged to Victoriano Guerrero. One of the agents offered to take Wienke to see the spectacular property. The following day they headed for the land subdivided into tracts, ranging in size from 10-acres upward.

The moment Wienke saw Moss Beach, he fell in love with the most breathtaking views he had ever seen. He marveled at th deserted beaches. He stood on the windswept cliffs, breathed the fresh salt air and knew it was nothing short of magnificent.

All that was for sale, and it could be his.

Wienke walked from one end of Moss Beach to the other as a flood of ideas rushed through his mind. He was mainly concerned with how he could afford to purchase 3,000 acres. Finally, as he lay on the cool white sands, Wienke focussed on one really good idea–that of creating a fabulous resort for San Franciscans at Moss Beach.

Surely, Jurgen Wienke was embellishing his story as he told it to Captain Lovdal; he had probably been telling it for a long time now, refining and sharpening here and there.

According to Wienke, the day after his first visit to beautiful Moss Beach, he was in San Francisco scanning the local newspapers. In one he found an ad announcing the West Shore Railway’s plans to build an iron road along the coast linking San Francisco with Santa Cruz. This was unbelievable news, such a coincidence. Encouraged, he rushed back to the Halfmoon Bay Colony office and purchased Moss Beach.

He did have an ace in the hole. He had recently married Meta Paulson and she was a cousin of Claus Spreckels, who already owned land on the Coastside. Claus Spreckels was known as the “sugar king,” and he was a very rich man. Where else to take his lovely new wife on a honeymoon than this “new land” called Moss Beach, a place with rarely seen beaches, more artful than real, a place that words could not describe.

In this inspirational setting, Jurgen Wienke dedicated himself to turning Moss Beach into the most beautiful resort on the coast of California. Captain Lovdal, who, with great regret had to tear himself away from Moss Beach to accept a new assignment on another vessel, agreed that Wienke’s dream had come true.

But to truly complete his dream, a railroad had to connect isolated Moss Beach with San Francisco. That part of the plan did not come true. Although the Ocean Shore Railroad came the closest to completing an iron road, the company couldn’t compete with California’s intense love affair with the new fangled automobile that took its passengers to explore new resorts much farther away.

Although the Wienkes sold some of their property, the tranquil days at Moss Beach were numbered. The flow of distinguished guests stopped coming; one day flames engulfed the Moss Beach Hotel, and a new era began.

————–

To see more photos of Moss Beach and the J. F. Wienke family, please visit the San Mateo County History Museum in Redwood City.

For Museum info, click here